Don’t you wish you had riskier projects? (Part 2)

Yesterday, I told you all how wonderful risk is. But it is fair to say that most of us work very hard to get rid of risk from our projects. Why this difference?

Yesterday, I told you all how wonderful risk is. But it is fair to say that most of us work very hard to get rid of risk from our projects. Why this difference?

Well, I think it is because there are two broad types of risks in a project. The first type is one that we all should try to reduce. It’s to do with competence, with doing our job well, with checking we are putting the project in the best position to be a success.

The second type of risk is the one I like. It’s to do with the change we are trying to bring about, the effect we are trying to have on the world outside our project. It’s the risks that you can’t get rid of, because they are part of why you are doing the project.

But because as project managers we have to deal with so many risks of the first type, we seem to get stuck in the mindset that risk is bad, that risk must be removed, that we have to play it safe. But trying to play it safe may be the most dangerous thing you can do.

Let’s look at these two types of risk. The first type are risks that we can and should get rid of. If you are creating a new product, of course you’d do market research to find out if there is demand for it. If you are putting in place a new business process, of course you’d talk with users to find out what they want from it.

To put it bluntly, of course you’d do your job. A lot of the risks we can easily get rid of in a project are really around making sure we’ve done our job correctly, and around making sure others in the business have done theirs. So of course we need to be interested in getting rid of these risks.

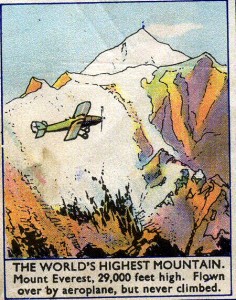

It’s like climbing Mount Everest. Before you go, you do your research and decide that it’s probably best to pack warm clothes. You may even investigate further and decide a few bottles of oxygen will come in handy. You make the preparations that get rid of the risks that can be got rid of.

But that still leaves the second type of risks. We may know there is a market demand for a new product – but will your product actually be successful? We may know what the users have told us they want from a new process – but will they actually use it?

These are the risks we can’t get rid of. Yes, we can do everything we can to create a product that meets the apparent needs of the marketplace, but we can’t know people will buy it. We can do everything we can to produce a process that is simple and easy to use, but we can’t know users will switch to that from what they already know.

Going back to our Everest metaphor, you can wear cold weather gear, carry oxygen, and make sure all the equipment you could need is available. But at some point you actually have to go out and climb the mountain, facing the dangers of the cold, the thin air, the strong winds, and the avalanches.

In other words, before you set off on your adventure, you make sure you have taken all the sensible precautions – and then you set off to face the danger anyway.

And there’s actually a good reason for that. Setting off to face the danger only makes sense if the rewards for overcoming it are significant. Those rewards, whether they are financial, social, personal, whatever, are the reason for facing the danger – the value of that payoff is weighed against the danger in achieving it.

In the same way, we weigh up the possible rewards of a successful project – be it increased profit, reduced costs, and so on – against what we are risking if the project fails – wasted money and time, lost opportunities, and so on.

So risk is good – at least, the right type of risk is. If there is a high risk project that we can do cheaply, then we definitely should. The concept of expected value (here’s an example of expected value in poker) comes into play here – though the probabilities involved with success and failure of projects tend to be harder to estimate!

For a business running a lot of projects, they can almost treat their projects as a gamble – they will stake a certain amount of ‘value’ (money and time) to try and achieve a larger amount of ‘value’. If the probability stacks up that you are making a profit, then do the project – accept the risk, embrace it.

Now, all of this makes sense if we are a business looking at risk, and trying to find a sensible way to deal with it. But what about just us, as project managers? It’s all very well knowing the second type of risk is different for the business, but is it different for us? Well, it all depends – and that’s what I’ll talk about tomorrow.

(Image courtesy of psd. Some rights reserved.)